Old Dog, New Tricks

It’s Mother’s Day, and I’ve left my family to be with strangers in the former parking lot of a flight school. A sea can is emptied, leaving a line-up of motorcycles outside to choose from. Although they’re mostly identical, we race to stand beside the special one we’ve picked from the pack. Bikes have a way of introducing you to people outside your circle, making today’s formalities with my classmates a little less painful. Patiently we wait. Our instructor hums through the boring bits while a motorcycle rips up the main drag beside us, towing our collective attention span along with it. Left behind until further instruction we remain, silently cheering for the escape artist we all wish we could be.

In New Brunswick, Canada, to obtain your motorcycle license you must pass a mandatory weekend skills and training course. It attracts all kinds of people: those who already know how to ride, those who think they already know how to ride, and people like myself who can no longer sit passively on the back and watch the world go by.

With opening exercises we walk our bikes forward to feel the weight and balance of the frame as it complies to our stride. Our instructor, who last evening sat slouched and bored in the classroom, has come alive in the fresh air, gesturing commands with his full body against the competing noise of traffic. He drills us with questions I know all the answers to and I shout back like a proud ‘A’ student. I’ve memorized all the handouts and know every written rule. When it’s time to fire up the bikes eleven engines start in unison, while mine struggles to care. I look around desperate for a helpful face and lock eyes with the guy beside me. “Turn on the fuel,” he says, as his bike purrs proudly underhand. Right!, I nod. F.uel, I.gnition, N.eutral, E.ngine, FINE; I repeat the order in my head like a broken record. This time the bike starts but instantly surrenders before I recall the next step in my memorized routine. I quickly try again, but the eagle eyed instructor is on to me. “I have one like you in every class I teach,” he says. “You’ve got to get out of your head and feel it.” After a day of lagging behind the class, I don’t feel it. I go home discouraged, but remain happy I’m in the course. I remember thanking the sun for showing up that day, because it kept the cold off my back and I needed a win.

To feel it more I start reading Elspeth Beard’s book, ‘Lone Rider’ and search the pages for any indication she also may have struggled. The book offers no instant resolutions except to provide a welcome distraction during breaks. In class we pair up and push each other on bikes down a straight line. In the past, as a passenger on Tom’s bike I excelled at pushing him around campgrounds, out of gas stations, through parking lots, toward hilltops, and alongside the road, tricking his vintage bike into motion. Out of the gate I’m good at something, and feel strong and confident as I’ve already mastered this routine. The 6 ft man I push in class today seems surprised at the hidden talent emerging from my small frame.

Our class graduates to a group ride around the perimeter and I place myself at the back of the line so I don’t hold anyone up. They appear to be having fun while I’m satisfied I haven’t stalled the bike in first gear. Slowly I round the final lap, slide across the finish line, and into the pavement. Instantly I regret my position at the back of the line, as everyone who arrived before me has a front seat at my performance. On my behalf, the instructor uses this as a teaching moment, and demonstrates how to pick up a dropped bike. I’m told everyone drops a bike at some point but I’m the only ‘everyone’ in this class.

After a break we re-group and take on our next set of trials. I bolt toward the bike I’ve been using, feeling a bond now that we’ve been through tough times together. Instinctively, the instructors glance over at me, breaking form. “You have to pick another bike. It’s important to get used to many types of bikes,” they say. I know it’s a cover for their real concern, that I’ll inflict damage on their only showpiece, the newest unscathed bike in a fleet of duplicates. The guy beside me hears this, and jumps on the chance to take my bike, while I swap out for his leftover wheels.

On day three my ski pants and winter gloves are pulled out of retirement and I wear them while snow falls to the ground. I’ve somehow managed to become a worse rider overnight and struggle to get my bike in gear. As the class parade in a non-stop circle around me, I’m propped stationary in the middle with a bike on its centre stand. Instructors stand on either side of me, coaching in bouts of frustration. All I can think about is a 25 cent mechanical horse I used to beg my mom to let me ride on at the mall. In my mind I throw in more quarters to get this horse moving. When I’ve successfully mastered shifting again we all take a break. I head to my truck to blast heat on my numb hands.

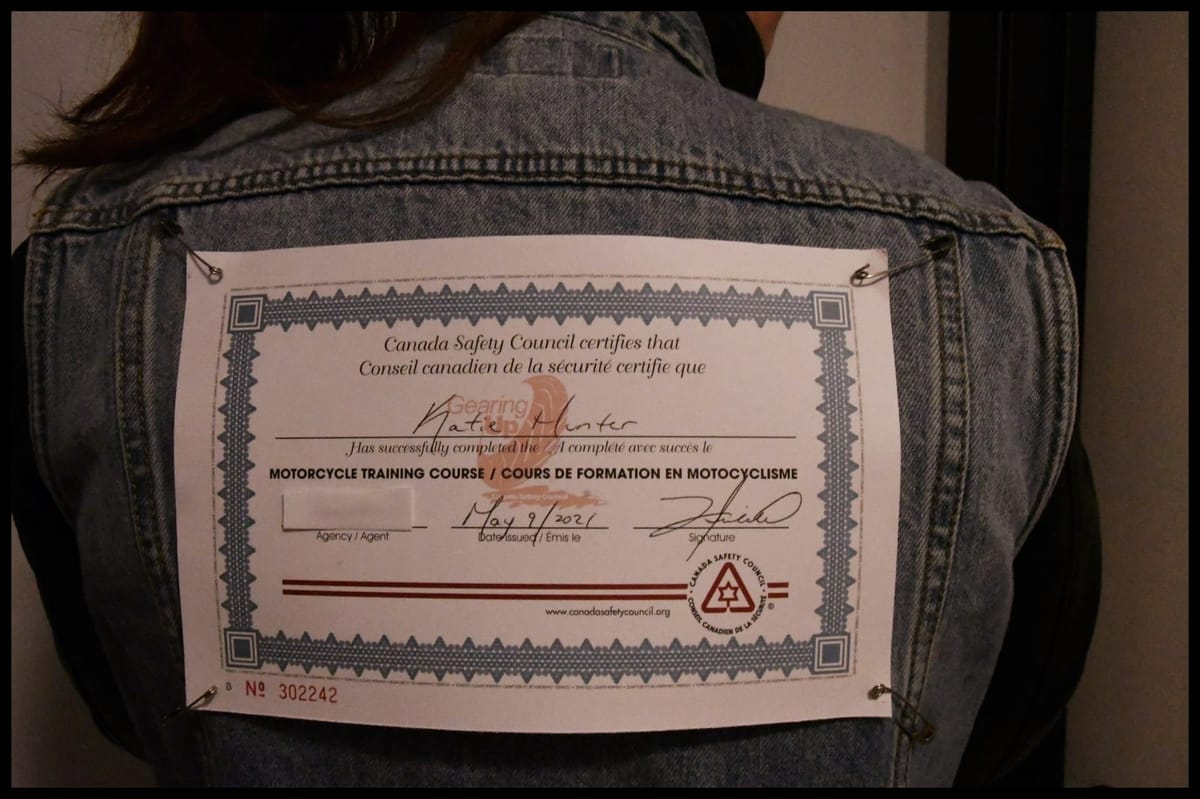

Back on pavement our instructor teaches us how to swerve and I teach him how to survive. Standing bravely beside an orange pylon he yells at the last second which direction to take. I approach his yells and swerve toward him, watching him sidestep as I correct myself just in time. Luckily, he’s quick on his feet and dodges our collision. My head fills with spaghetti western scores as I imagine he’d make a great extra, avoiding the shower of bullets in the dance of a shootout. After this extreme showcase, the course offers redemption through low gear maneuvering. I bend and loop expertly around figure 8’s and zig-zag with ease through pylons. Starting to feel the bike underneath, I excel in the control and balance exercises. Through nothing short of a miracle, I pass the course along with the class.

Now on my own and under no pressure, I drive to the stop sign at the end of my street and back. Gradually, I creep along the roads and chase dirt paths I can’t reach in a car. At one point, I break past the familiar circuit of the neighbourhood and cross the bridge into the city. I feel exhilarated, as if leaving home for the first time. With no one to yell, “Don’t dump the clutch” it’s easier to relax and find focus. I nonchalantly re-start my bike when I stall, and stay calm when the gas tank drains before my expectations.

Tom says learning to ride a bike is all about saddle time, so I trail behind like a duckling mimicking his habits, for better or worse. Patiently he waits as I push my way up hills meant for bikes with more power. I no longer care if traffic is behind me, and at one point I stop counting what gear I’m in. All of my puttering on nothing short of a ride-on lawn mower, accumulates into my goal of 10,000 km my first short season. We celebrate with cake, and I move onto a bigger bike like a crustacean discarding its old shell.

That first year feels so long ago, it’s as if this story belongs to someone else. Always the passenger, I didn’t take control of a bike until I was older, needing a getaway vehicle of my own. When you’re young and learning to ride, mistakes are frequent and expected; without youth on my side I had to catch up with the pack. Learning to ride didn’t happen overnight, or on a weekend course, and for that i’m grateful or i’d be bored of it already. Four years past my rodeo of mishaps and I’ve transformed into a great rider: climbing into the clouds of Mount Washington, pushing through flooded roads in Vermont, blasting down the Florida turnpike on a thumper as Miami hit rush hour, and riding through Canada as far I could reach within a two week span. Every time I’m out it’s a new challenge that’s a little less uphill than before, and instead of Tom waiting for me, I sometimes get there first.